South Sudan, the world’s newest nation, has been ravaged by ongoing civil conflict, drought, and crop failures since its independence from Sudan in 2011. An influx of humanitarian assistance was rushed to the country following a declaration of famine in February 2017. Four months later the famine was officially over, but widespread malnutrition and food insecurity persist, raising the question: has the life-saving emergency response achieved its goals?

Action Against Hunger is a global humanitarian organization addressing the causes and effects of hunger, with a focus on child malnutrition and clean water. Operating in nearly 50 countries, Action Against Hunger has worked in South Sudan since 1985. Mickey Leland International Hunger Fellow Sarah King was placed with Action Against Hunger in South Sudan from September 2017 to August 2018. Read on to hear about Sarah’s work administering a nutrition survey in Aweil East state, and how she hopes her work will improve the lives of the people in South Sudan.

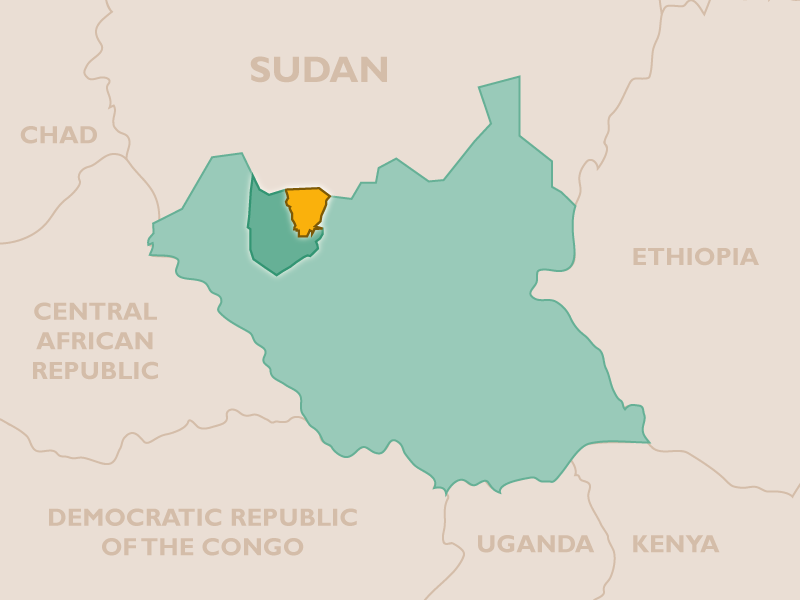

Map of South Sudan, showing Northern Bahr-el-Ghazal area in darker green and Aweil East state in orange.

“Two Indicators”

Since civil war broke out in 2013, South Sudan has experienced a protracted emergency with an unstable economy, limited infrastructure, and widespread political insecurity. As a result, communities throughout the country have suffered severe food insecurity with accompanying high rates of malnutrition. Action Against Hunger, a non-governmental organization specializing in nutrition interventions, has worked in South Sudan since the country’s independence, providing integrated nutrition, food security, and hygiene/sanitation services.

Action Against Hunger implements public health surveillance and evaluation activities to assess the impact of its work and to closely monitor the situation on the ground. Part of its surveillance activities includes Standard Monitoring and Assessment of Relief and Transition surveys, also known as SMART surveys. SMART was developed in 2002 to assess emergency situations, either as an initial assessment or as a yearly monitoring tool. The survey is based on two indicators: the nutritional status of children under five years old and the mortality rate of the general population. These two indicators are used because they reliably provide signs of the severity of a crisis for an entire community.

Leland Hunger Fellow Sarah King (far right, facing away) with colleagues from Action Against Hunger surveys children’s height as a measure of malnutrition in Aweil East state in South Sudan.

“Over 450 households in just seven days”

For the last year, I had the opportunity to work with Action Against Hunger in Northern Bahr el Ghazal, South Sudan. As part of my time with the organization, I co-managed a SMART survey in July in Aweil East, a state found in Northern Bahr el Ghazal. With a team of twenty-four data collectors we traveled to thirty-five villages throughout Aweil East, visiting over 450 households in just seven days. In each household we assessed children between the ages of 6-59 months. We measured each child’s height, weight, and mid-upper arm circumference, measurements used to determine whether the child was experiencing acute malnutrition. Their caregivers were then asked a series of questions related to mortality, illness, sanitation, and food security within their household. At the end of the survey the data was compiled, analyzed, and submitted to South Sudan’s Nutrition Information Working Group for validation.

The survey discovered an estimated global acute malnutrition rate of 21%. Just over two children out of ten experienced wasting—they either did not have enough food to consume, or they had an illness leading to sudden weight loss. This type of malnutrition has devastating consequences, including increased risk of further illness and death. With a global acute malnutrition rate this high, the level of malnutrition is classified as “Critical” based on the World Health Organization’s emergency classification thresholds. This is the last threshold on the World Health Organization’s scale.

Additionally, the survey found high rates of food insecurity, with 63.4% of households experiencing poor food consumption and 25.9% experiencing borderline food consumption. In addition, 57% of households experienced moderate hunger and 39% experienced severe hunger. The data indicates that households in the region have significant challenges accessing food and are frequently unable to achieve nutrient-adequate diets with the available resources.

“It is an immense responsibility and privilege to participate in this work on a daily basis”

The survey’s results will hopefully lead to sustained donor support in the region and the continuation of integrated nutrition and food security services. But I believe the survey’s most important finding is that even with the presence of humanitarian assistance in the form of health, nutrition, sanitation, and food security services, two out of every ten children still experienced life-threatening malnutrition. While the programming taking place is certainly staving off the worst, it is not enough.

This SMART survey and surveys like it force those of us in the humanitarian community to take stock of our activities, to ask hard questions, and to push ourselves to improve. There are no easy answers and it is certainly an iterative process—one my co-fellow, Grace, I, and the entire Action Against Hunger team prioritize every day. For Action Against Hunger, this looks like continually introducing and testing initiatives like Mother MUAC, gender-based violence training, and demonstration gardens to complement the standard emergency nutrition programming being delivered. It means exploring new avenues of collaboration between teams within and outside the organization so malnutrition is holistically treated. And it has us looking critically at our actions and potential areas of failure. Public health surveillance plays an integral role in emergencies because the last thing we can afford is to make the situation worse. It is an immense responsibility and privilege to participate in this work on a daily basis. As the first year of the fellowship comes to a close and I begin to look toward the coming year, I am cognizant of the role I have been afforded and hope that I too can use the findings of the survey and the year to improve on my own work and do more.