Photo: Steve Evans

South Sudan is the world’s newest nation, and one whose short official history has been marked with violence and hunger. Two years after declaring its independence from Sudan in 2011, the nation entered a period of civil war and ethnic violence which continues to this day. In February 2017 the United Nations made a formal declaration of famine for parts of the country, and South Sudan is one of the examples put forth in the 2017 State of Food Security and Nutrition in the World Report of how rising levels of hunger across the world are largely attributable to conflict and climate change. Leland International Hunger Fellow Grace Heymsfield, partnering with Action Against Hunger, has spent the past four months working in South Sudan on a pilot project to highlight how the prevalence of violence, particularly gender-based violence, is preventing people from accessing nutrition programs.

Gender based violence (GBV) is a pervasive human rights issue exacerbated in emergency contexts. Nutrition may not be the first thing that comes to mind when discussing GBV, but gender equity is foundational to food security[1]—availability and adequate access at all times to sufficient, safe, nutritious food to maintain a healthy and active life. To enhance accountability of humanitarian nutrition organizations towards GBV awareness and equity, Action Against Hunger (AAH) is piloting a GBV project in three program countries: Bangladesh, Mauritania, and South Sudan. As part of this pilot, I participated in an AAH workshop in Juba, South Sudan, to identify linkages between nutrition and GBV in South Sudan, as well as next steps at the field and national levels.

In 2009, 41% of women and men in South Sudan reported experiencing GBV within the last year [2]. There is limited information about the changes in gender relations in South Sudan since conflict escalated in July 2016, but reported incidents of sexual violence since then have markedly increased [3]. Women bear a disproportionate burden of household chores and in some areas report that they go out to collect food or firewood knowing the risk of rape [4]. A CARE assessment conducted in September 2016 revealed that women and girls had reported fleeing to Uganda to escape the high levels of sexual violence [5]. Thus, actors like CARE estimate the prevalence of GBV in South Sudan at much higher than 41%, as populations in many parts of the country are in flux and are disproportionately female, particularly in vulnerable age groups [6].

Despite its pervasiveness, GBV is not considered a life-and-death issue, and thus a priority, by many nutrition actors. To take another cross-cutting sector as an example, the nutrition community is increasingly discussing integrating WASH (water, sanitation, and hygiene) and nutrition interventions. Could the same approach be taken with gender inequality, and at its extreme, GBV?

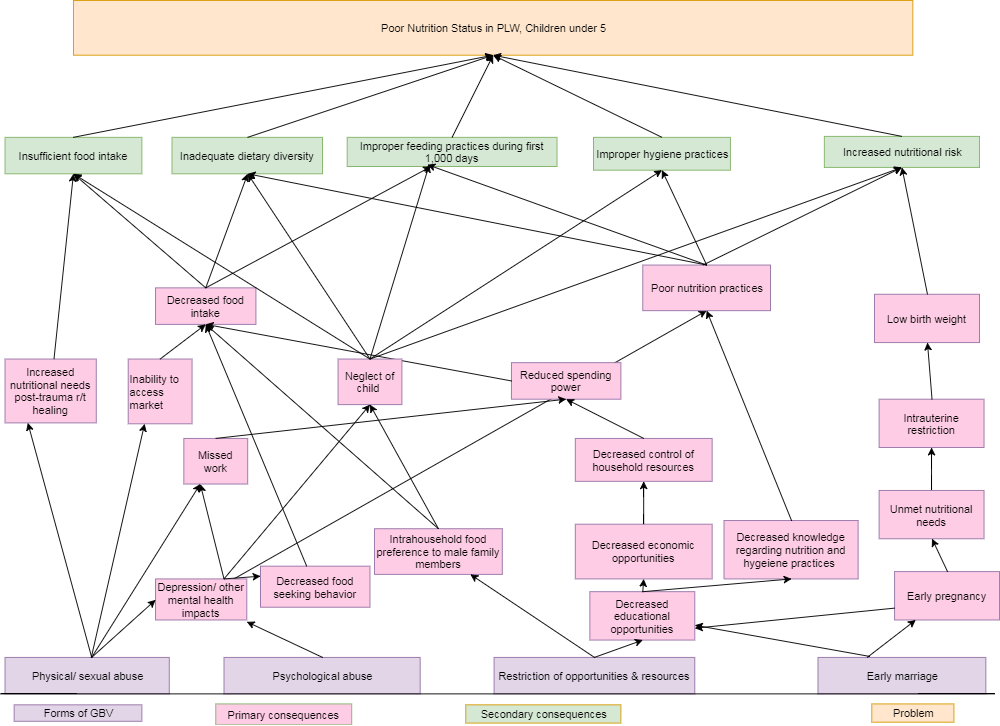

My co-fellow Sarah King and I mapped how various forms of GBV (physical/sexual abuse, psychological abuse, restriction of opportunities & resources, and early marriage) contribute to risk factors (including insufficient food intake, inadequate dietary diversity, improper hygiene, improper feeding, and increased nutritional risk) for the overall problem actors like AAH are fighting: poor nutrition status in pregnant/lactating women and children under 5.

This problem tree (above) illustrates how GBV, as the most extreme form of gender imbalance, affects major causes of undernutrition in our communities. Namely, GBV contributes to poor nutrition status through:

- Compromised ability to access food: negative effects of security threats and/or emotional stress on food-seeking behaviors; low purchasing power or lack of “permission” to buy food

- Restriction of opportunities: adolescent girls being discouraged from attending school; increased dependence on exploitive relationships for food

- Vulnerability during critical life stages: early marriage and pregnancy can increase risk of low-birth weight delivery secondary to intrauterine restriction, increasing nutritional risk of both mother & baby

- Directly increased nutritional needs: hyper-metabolism post-injury and burn, resulting in increased energy expenditure and increased energy needs; opportunistic infections post-trauma resulting in even higher caloric requirement; decreased appetite secondary to stress

It is clear that inequity and GBV underscore many barriers to access and uptake of nutrition programs. Championing gender equality would improve coverage of these programs, as well as the overall nutritional status of our communities. As part of this pilot project, Sarah and I will be involved in incorporating GBV material in feedback mechanisms at our nutrition clinics, focus group discussions, and staff trainings. Through this problem tree, I can see how gender inequity and GBV affect many of the issues I am focusing on during my field year- general program management, mother-to-mother support groups, and SMART surveys that will inform strategies for the national nutrition cluster. As we gain a clearer perspective on GBV’s role in malnutrition from staff and beneficiary feedback, I am excited to carry out my field year with a gender equity lens.

Notes

[1] https://www.wfp.org/node/359289

[2] UNIFEM Gender-based Violence and Violence Against Women: Report on Incidence and Prevalence in South Sudan. 2009

[3] http://reliefweb.int/report/south-sudan/south-sudan-opening-remarks-delivered-un-resident-coordinator-south-sudan-eugene

[4] http://insights.careinternational.org.uk/publications/inequality-and-injustice-the-deteriorating-situation-for-women-and-girls-in-south-sudan-s-war

[5] http://insights.careinternational.org.uk/publications/inequality-and-injustice-the-deteriorating-situation-for-women-and-girls-in-south-sudan-s-war

[6] http://insights.careinternational.org.uk/publications/inequality-and-injustice-the-deteriorating-situation-for-women-and-girls-in-south-sudan-s-war